The federal cases against Pfizer and generic drug manufacturers of generic Depo Provera have been consolidated in the northern district of Florida. Kansas City Depo Provera Lawyer Jeffrey Carey has extensive experience with defective and dangerous drug litigation and established relationships with counsel in Florida. The same judge is overseeing the 3M combat ear plug litigation.

If you have developed meningiomas after taking Depo Provera you have a claim for damages against Pfizer. A MDL stands for multi-district litigation. Under a MDL you will file your case in a federal district court with jurisdiction to hear the case. Most Depo Provera meningioma cases arising in the greater Kansas City metropolitan area will be filed in the Western District of Missouri or the District of Kansas. The initial phases of the case will be handled by the judge in northern Florida. Then, presuming cases survive inevitable motions to dismiss or for summary judgment, there is typically a settlement offer to the members of the MDL class. Importantly, if you do not want to take what is offered at that time you can proceed with your case here locally and we can help.

It is early in the process and litigation but it appears that Pfizer has known for a significant period of time that the risk of developing meningiomas is increased substantially by exposure to Depo Provera. The FDA has been typically slow to respond to evidence accumulating about the connection. When the British Journal of Medicine published their bombshell report on the connection, the FDA has continued to refuse to issue warnings to US consumers even while the lawsuits pile up.

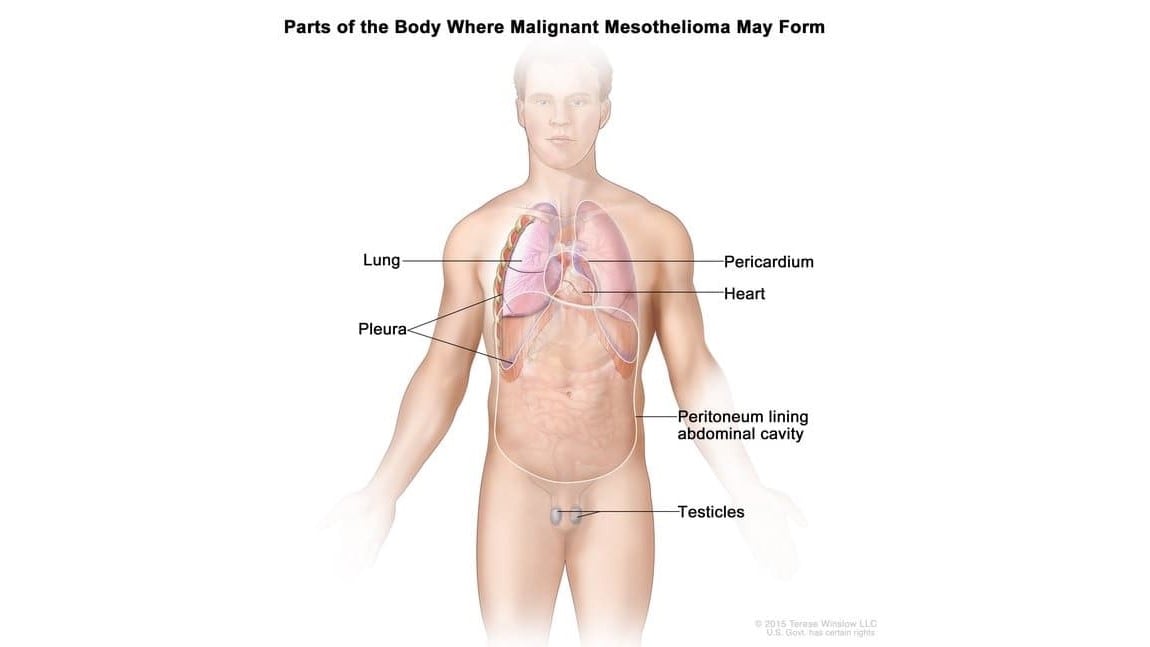

Lawsuits against Pfizer for meningioma developing after long term depo provera use will typically involve claims for failure-to-warn, defective design, negligence, misrepresentation, and breach of warranty. As injectables, the warnings would typically have been given by a “learned intermediary” The center of these cases is the fact the Pfizer knew about the enhanced risk of cancer caused by its drugs and hid that information from the public to preserve profits.

Depo Provera was a famously difficult approval process when it first occurred. As far back as 1988, after a 20 year approval process, the FDA warned that the drug was causing cancer in testing animals according to a publication by the National Institute of Health.

If you or a loved one have developed meningioma after taking Depo Provera, Jeff Carey can help. Call 816-246-9445 to schedule a free no-obligation consultation.

Google Plus

Google Plus